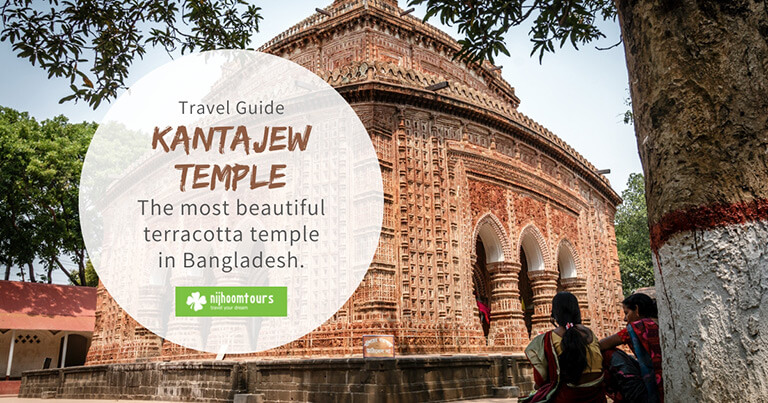

Nestled in a remote corner of Bangladesh, the Kantajew Temple, also known as Kantanagar Temple, Kantaji Temple, or Kantojir Mondir, is a magnificent testament to the country’s rich cultural and architectural heritage. Built by the royal family of Dinajpur in the early-18th century and dedicated to their family god Krishna, it exhibits a vitality of mature terracotta art at its best in Bengal.

The Kantaji Temple attracts visitors from far and wide for its religious importance and architectural splendor. In this article, you’ll get all the details about Kantajew Temple from historical, religious, and travel perspectives.

Table of Contents

- Location of Kantajew Temple

- History of Kantajew Temple

- Architecture of Kantajew Temple

- Terracotta Decoration of Kantajew Temple

- Terracotta Work in Bengal

- The Artisans of Kantajew Temple

- Festivals at Kantajew Temple

- Visiting hours

- Entry fees

- Visiting Kantajew Temple

- Frequently Asked Questions

- References

Location of Kantajew Temple

Kantaji Temple is located about 12 miles / 19 km north of Dinajpur town along the Dinajpur-Tetulia highway and about a mile west of the road across the Dhepa River in an island village known as Kantanagar.

History of Kantajew Temple

Kantajew Temple was constructed in two generations in the early-18th century by the feudal landlord of Dinajpur, Maharaja Prannath, and his adopted son Raja Ramnath during the British colonial period in Bengal.

The Finishing of the Construction

A four-line Sanskrit inscription, written in old Bengali characters, is fixed on the northeastern corner of the temple plinth. It records its date of construction in a chronogram and the names of its builders with other minor complementary information. It reads:

“Sake bedabdhi kala kshiti pariganite bhumipa Prannatha Prasadanchatiromya surochito nava-ratnakhya masminya karyata Rukmini Kanta tushtoya samuchito manasa Ramnathen ragma Datta kantaya kantasya tu nija nagare tato sankalpo siddhya”

Which translates as:

“Raja Prannath began the construction of this well-built, elegant nava-ratna temple. Raja Ramnath (his son) dedicated it to Srikanta in his own town (Kantanagar) in order to propitiate the consort of Rukmini in the Saka year 1674 (1752 AD) with a view to fulfill his father’s wish.”

Thus it is confirmed that Kantajew Temple’s construction was finished in 1752 AD.

The Beginning of the Construction

In M. Martin’s “Eastern India,” written in 1838 AD, it is recorded that “In 1704, the first foundation of the temple was laid. In 1713, a larger building commenced, and in 1722 the foundation of the finest part was begun.”

Although Martin’s statement is not altogether clear and leaves much for guesswork, it seems likely that Maharaja Prannath, on securing an image of Krishna from Brindaban, installed it in a hurriedly built 16-sided, single-spired temple located to the north of the main temple in 1704 AD.

The construction of the Kantajew Temple’s main structure likely began in 1713 or 1722 AD. If it started in 1713, it took 39 years to finish. However, if it began in 1722, it took almost 30 years to complete.

However, it is pretty sure that Prannath started the erection of the temple but evidently couldn’t complete it during his lifetime because it took a long time to complete it. Prannath died in 1722 AD; therefore, the main temple’s foundation was evidently laid in the same year of his death or a decade earlier.

Founding the Kantaji Temple

During his reign, Prannath entangled himself in a bitter rivalry with his neighboring Zamindar (feudal landlord), Raja Raghabendra Roy of Ghoraghat. Consequently, Raja Raghabendra Roy falsely accused him of murdering his two brothers, oppressing his subjects, corruption, and insubordination to the Mughal Court. On receiving these allegations, the enraged emperor Aurangzeb peremptorily called Prannath to his court in Delhi to explain his conduct.

Thereupon he appeared at the emperor’s court with costly presents and convincingly proved the baselessness of the allegations leveled against him by his rival. Being satisfied, the Mughal emperor acquitted him of the charges and conferred on him the title of “Raja” (King) besides bestowing other costly presents.

Overjoyed at surviving a great crisis, Raja Prannath went on a pilgrimage to Brindaban to express his gratitude to his favorite God, Krishna. From here, it is said he discovered at dawn a beautiful Krishna image on the Jamuna river bank, as indicated to him by God in a dream.

He then reverentially collected the icon and floated down the river on a barge through Padma, Mahananda, and Punarbhaba till the barge automatically stopped at a place then known as Shymgarh and later renamed as Kantanagar, about 12 miles north of his palace in the town. Here he began the construction of the small single-spire temple in 1704 AD. and installed the Krishna image on it before embarking on his ambitious project of building the five-spire temple in 1722 AD.

Kantojir Mondir at Its Prime Time

It is on record that the Maharaja Girijanath used to maintain a vast herd of milking cows, known as “Gopaler Dhenu,” and that their copious quantity of milk, butter, and cream was offered daily to the enshrined deity in the temple as an unavoidable part of the ritual. This, in turn, supported an army of hungry parasites around the temple.

Lord Curzon, the Viceroy of India (1899-1905), is said to have drastically reduced the number of the cow herd to 75, which immediately triggered a strong protest by the devotees, sycophants, and the Maharaja. This eventually obliged the British government to withdraw this “highly irreligious and unjust” decision and to increase the number of milking cows from 75 to 300 instead of the earlier 3,000 heads of cattle.

Preservation Efforts of Kantajew Temple

Over the centuries, the Kantajew Temple has faced the ravages of time, weathering natural disasters, neglect, and human encroachment. However, significant efforts have been made to preserve and restore this architectural marvel.

Restoration by a British Collector

For want of attention, Kantaji Temple soon fell into disrepair within less than fifty years of its completion. George Hatch, the first collector of the Dinajpur district under British colonial rule in Bengal, had it thoroughly restored sometime in the late 18th century.

Restoration by Maharaja Girijanath Roy Bahadur

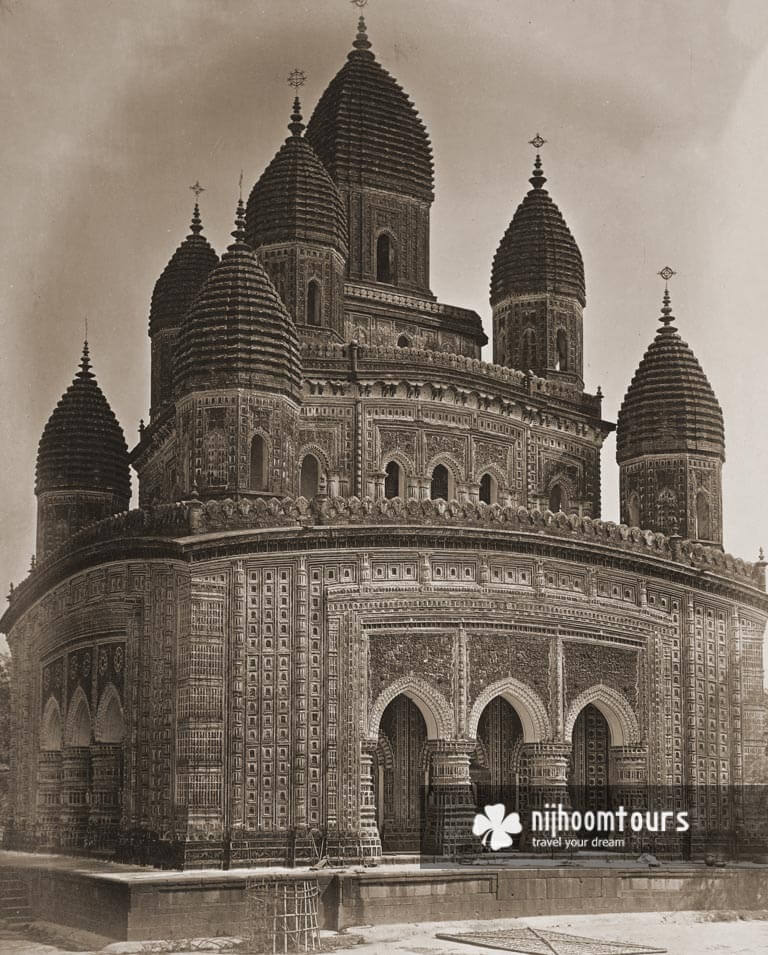

Kantajew Temple fell into considerable disrepair over centuries and was severely damaged during the devastating earthquake in 1897 when all its nine elegant spires collapsed. A descendant of Prannath, Maharaja Girijanath Roy Bahadur (Ruled 1882-1919), spent considerable money to restore it. However, the spires were not restored.

Inclusion in The Tentative List of UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Kantajew Temple has recently been included in the tentative list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites, which signifies its exceptional value and unique heritage. This recognition brings attention to the temple’s historical and artistic worth globally and acknowledges the temple’s potential for future inscription as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It elevates the temple’s status, encourages preservation efforts, and reinforces its position as a treasure of global heritage.

Architecture of Kantajew Temple

Originally, Kantaji Temple was a three-storied ‘nava-ratna’ temple or a temple crowned by nine ornamental towers or ‘jewels’ (spires) which imparted to it an appearance of a huge ‘ratha’ or an ornate chariot resting on a high plinth. It was provided with an arch opening on all four sides to let the devotees see the enshrined deity inside from all directions.

The 52′-0″ squire-shaped Kantajir Mondir is built on a center of a 63′-0″ squire stone plinth which rises 3′-3″ above the ground. The plinth is approached by a short stone staircase, set in the middle of its western side, leaving a strip of open space of about 5′-6″ all around the shrine.

The curved corniche of the ground floor, dropping at the corners, rises in the middle to a height of 25′-0″ from the plinth, while that of the first floor rises to a height of 15′-0″ and that of the second floor rises to a height of 6′-0″. On top of the second floor the remains of a 3′-0″ high squire base of the missing ornamental tower still survive.

There are small square cells at each of the four corners of the ground and first floors for supporting the heavy load of the ornate octagonal corner towers above. The temple accommodates four rectangular corridors on the ground floor around the prayer chamber.

On the ground floor, three multi-cusped arched entrances are on each side, each separated by two richly decorated brick pillars. A narrow staircase strip is built into the western second corridor and winds up through its dark passage to the first, second, and third stories.

Terracotta Decoration of Kantajew Temple

Every available inch of its wall surface, from the base to the crest of its three stories, both inside and out, is decorated with an amazing profusion of figured and floral terracotta art in unbroken succession.

The vast array of subject matter includes the stories of the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, the exploits of Krishna, and a series of extremely fascinating contemporary social scenes depicting the favorite pastimes of the landed aristocracy.

The astonishing profusion, the delicacy of modeling, and the beauty of its carefully integrated friezes have seldom been surpassed by any mural art of its kind in Bengal. However, one distinctly delightful aspect of the fabulous terracotta ornamentation of Kantajew temple is its restraint in depicting erotic scenes. In this, it is unlike Orissan and South Indian temples.

The terracotta embellishments on the Kantanagar temple walls are of a totally different nature from the other terracotta works found in the Buddhist temples from the Pala dynasty from the 7th-8th century. They represent a highly sophisticated mature art with a very carefully integrated scheme of decoration.

Contrary to the earlier tradition of isolated and somewhat unrelated composition, the art in this temple was composed of several individual plaques, integrated into an extended composition so that the entire space followed a rhythm.

Terracotta Work in Bengal

In a predominantly deltaic area like Bengal, the evolution from remote antiquity of indigenous terracotta art was a logical outcome to a land without stone. This inexpensive plastic art in this region is rooted as far back as at least to the Pala-Chandra period (8th-12th century), when the Buddhist temples at Paharpur, Mainamati, Vasu Bihar, Sitakot, and other contemporary monuments were enlivened with terracotta plaques, presenting the popular folk-art of the period. The deep red brick buildings, covered with a wide variety of terracotta decorations against the lush green background of the country, obviously had great appeal to the builders and the artisans.

A distinctive Bengali culture emerged in the land during the period of independence under the Sultans for over two centuries between 1338 AD and 1576 AD, primarily manifesting in vernacular literature and building art. During this period, the political and cultural life of Bengali people found its fullest expression in the flowering of their vernacular literature and fostering a distinctive indigenous building art. This regional trend of intense cultural activities contributed to the drift of Bengal apart from the main current of Delhi. Terracotta art during this period also flourished and matured.

The plaques at Paharpur and Mainamati are larger, more archaic in character, and are set in recessed panels along the terraces without any sequence or order. However, terracotta art of the medieval period, embellishing late temples, is of a totally different nature. It represents a highly sophisticated mature form of art, with very carefully integrated designs executed with infinite care and significant refinement of details, clearly betraying inspiration from the refined surface decorations of the Sultanate monuments of Bengal.

The largest number of surviving temples in Bengal belong to the late medieval period or date from the Mughal period and later. The landed aristocracy or wealthy merchants primarily patronized the erections of these temples in society. After the British secured the Dewani of Bengal in 1765, many old landlords lost their estates, and a plethora of new landlords arose who were from different from the royal families as the previous landlords. These new landlords started building these temples to glorify their names. They heavily used terracotta works in their temples.

The Artisans of Kantajew Temple

The name of the architects and the artisans only appeared on the temples after the middle of the 18th century. There might have been social inhibition against the recognition of temple architects and artisans in those edifices, who invariably came from lower strata of society.

It is now known that the artisans of the “sutradhar” community were the architects and sculptors of Bengali temples. They came from the Hindu “Sutradhar” families, bearing the present-day surnames Das, Pal, De, Datta, Sain, Chandra, Bardhan, Ray, Maiti, Sil, Ram, Kundu, Kar, Karmi, and Sen.

Sutradhar literally means one who holds a cotton thread for measuring something, which generally came to be associated with the carpenters, who were skilled in woodworks but, as we have seen, also specialized in temple-building and decorating its wall surfaces with rich terracotta art.

Although the exact name of the architects and artisans of Kantajew Temple is unknown, it can be said that, unlike some popular belief, these artisans were local Bengali people, not imported from another faraway land.

Festivals at Kantajew Temple

Kantaji Temple is a vibrant center for religious celebrations and festivals, attracting devotees and visitors from far and wide. The temple’s sanctity and historical significance make it a popular destination for Hindu festivals.

Raas Festival

On the full moon of “Kartik” (November) every year, the Raas Festival is celebrated at Kantajew Temple with great pomp. Amidst the jubilant celebration, the Kantajew idol, a representation of Radha-Krishna (Radha-Krishna Bigroho), from the main temple, is brought to the “Raas-Mancha” (a platform dedicated to the festival), about 200 yards west of the main temple, in the presence of thousands of devotees who journey from various corners of the subcontinent.

This age-old tradition, dating back five hundred years and associated with the Rajas of Dinajpur, calls for performing rituals on the night of the full moon. The festival transforms the entire region as a vast ocean of humanity congregates around the Kantanagar Temple. Pilgrims arrive in enormous numbers, traveling from India, Nepal, and all corners of Bangladesh, eager to partake in the joyous festivities.

Throughout this vibrant period, the temple authorities extend their hospitality to the visiting devotees by providing nourishing food and captivating entertainment. The air resonates with ritual songs and mesmerizing Radha-Krishna dances, delighting the attending pilgrims and upholding the rich traditions of temple festivities.

Apart from the religious ceremonies, the festival organizers also arrange a month-long mela (fair) within the temple premises. This attracts hundreds of traders from different parts of the country, showcasing their diverse products and wares to eager visitors.

Kantajew Temple is one of the three places in Bangladesh where the Raas Festival is celebrated, besides the Dubla Island in Sundarbans and the Raas Festival of the Manipuri Tribe in Sreemangal.

Dol-Jatra (Holi) Festival

An important festival observed at Kantaji Temple is Dol Purnima or Holi, the festival of colors. Celebrated during the full moon of Falgun (February/March), devotees come together to play with vibrant colored powders and water, symbolizing the joyous arrival of spring and the victory of good over evil.

The temple’s deity is placed on an old dilapidated square “Dol-Mancha” (a platform dedicated to the festival) during the festival, about 300 yards east of the main temple. The temple premises become a riot of colors as people immerse themselves in the festivities.

Visiting hours

Kantajew Temple is always open for visitors. You can enter the temple at any time of the day to visit.

Entry fees

Kantajew temple does not require any ticket for both local and foreign visitors. They will, however, require 100 tk. parking charge if you have a car with you. Consider giving some donations to the temple while visiting.

Visiting Kantajew Temple

Check out our Kantajew Temple Tour to visit the temple on a day tour from Dhaka with convenience and comfort. We also organize other multi-day tours in Rajshahi and Dinajpur Region featuring the highlights of the Northwestern Bangladesh. We are an award-winning local tour operator in Bangladesh specializing in organizing tours and holidays in Bangladesh for Western travelers, with numerous positive reviews on Tripadvisor. Contact us now for organizing your tour in Bangladesh!

Frequently Asked Questions

When was Kantaji Temple built?

Kantajew Temple was built between 1713 AD or 1722 AD and 1752 AD. It is not confirmed when the construction of the main temple started between these two dates.

How long it took to build Kantajew Temple?

It took either 30 or 39 years to complete the construction of Kantajew Temple.

Who built Kantahew Temple?

Maharaja Pran Nath, the feudal landlord of Dinajpur, started the construction of the Kantajew Temple. His adopted son Raja Ram Nath completed it.

Where is Kantajew Temple located?

Kantajew Temple is located in the Dinajpur District in Bangladesh, 12 miles / 19 km north of the Dinajpur town center beside the Dinajpur-Tetulia Highway.

What is the specialty of Kantajew Temple?

Every inch of the walls of Kantajew Temple is wrapped in stunning terracotta depicting epic Hindu stories and social life in the 18th century. It is the most beautiful Hindu temple in Bangladesh.